In Conversation: Manoj Dias & Tjimarri Sanderon-Milera

Words: Good Sport

Images: Ben Clement

Tjimarri Sanderon-Milera (TJ) is a proud Aboriginal man, born and raised in Adelaide, from the Narangga and Kokatha language groups, located on South Australia’s western coastline. TJ has been a 100m-400m track sprinter since his teens, creating opportunities to compete on the National Circuit and overseas for Australia. Throughout his sprinting career TJs encountered a multitude of pivotal experiences, good and bad, and is now channeling his learnings toward the new wave of young Aboriginal kids. TJ coaches fundamental skills to succeed not only in athletics, but within life itself. As an ambassador for lululemon, TJ continues to empower and build community within this younger generation to help them achieve their dreams. Through the University of Adelaide’s Wirltu Yarlu Aboriginal Education Program, TJ strives to break the inequality of education for First Nation people.

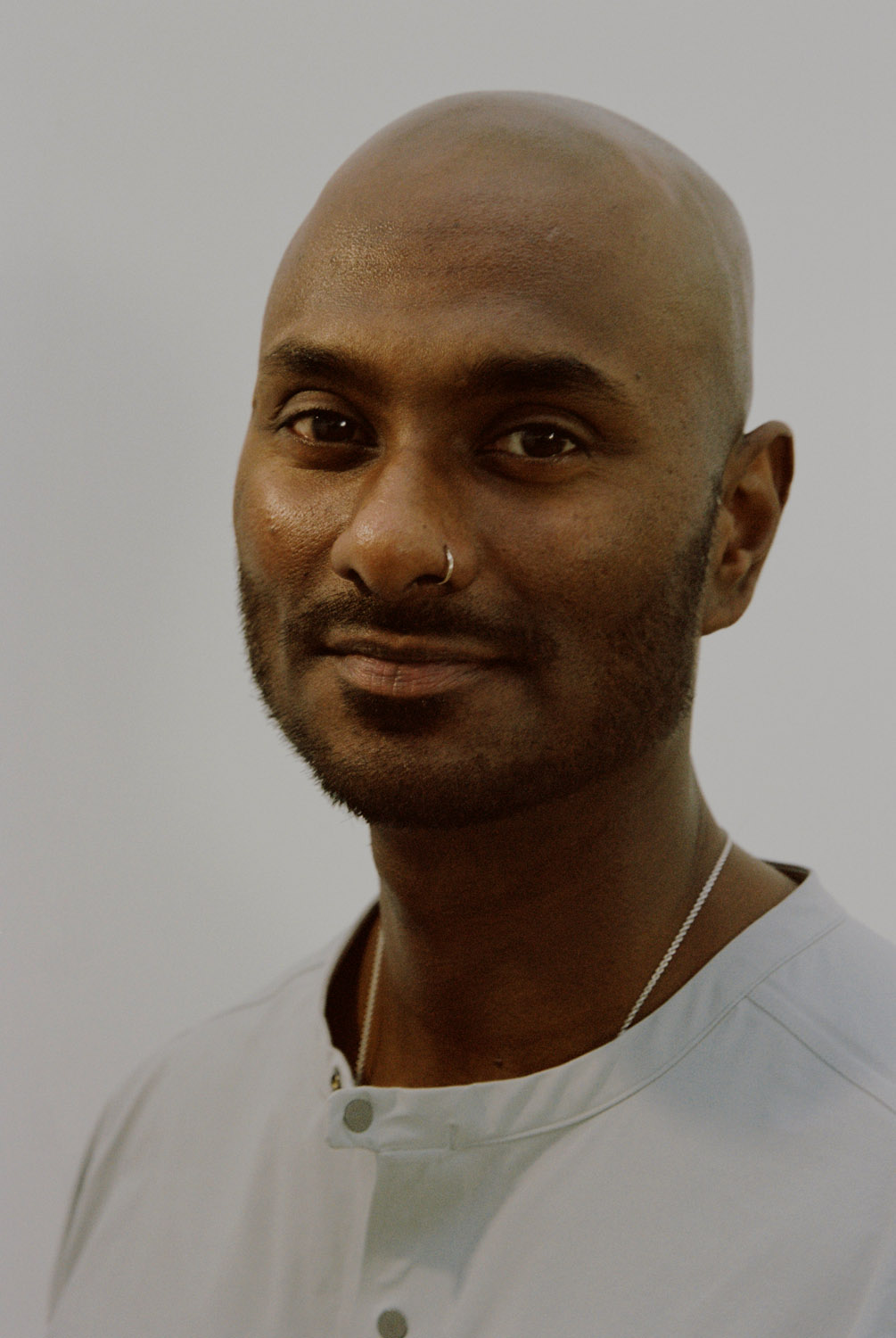

Born and raised in the Theravada Buddhist tradition, Manoj Dias is a speaker, coach and educator. Through mindfulness and meditation, Manoj has helped thousands of people around the world trade mania for pause, so that they may live fearlessly in honour of a happier and more meaningful life. As the founder of A—SPACE, Australia’s first multidisciplinary meditation studio, he walks this truth en masse with a family of one heart, having regularly taught in New York, Los Angeles and throughout Australia. Manoj became Australia’s first lululemon global yoga ambassador, a role he uses to champion more accessible and inclusive wellness experiences for the under privileged and marginalised.

The following conversation was proudly initiated and inspired by lululemon.

Words: Good Sport

Images: Ben Clement

Tjimarri Sanderon-Milera (TJ) is a proud Aboriginal man, born and raised in Adelaide, from the Narangga and Kokatha language groups, located on South Australia’s western coastline. TJ has been a 100m-400m track sprinter since his teens, creating opportunities to compete on the National Circuit and overseas for Australia. Throughout his sprinting career TJs encountered a multitude of pivotal experiences, good and bad, and is now channeling his learnings toward the new wave of young Aboriginal kids. TJ coaches fundamental skills to succeed not only in athletics, but within life itself. As an ambassador for lululemon, TJ continues to empower and build community within this younger generation to help them achieve their dreams. Through the University of Adelaide’s Wirltu Yarlu Aboriginal Education Program, TJ strives to break the inequality of education for First Nation people.

Born and raised in the Theravada Buddhist tradition, Manoj Dias is a speaker, coach and educator. Through mindfulness and meditation, Manoj has helped thousands of people around the world trade mania for pause, so that they may live fearlessly in honour of a happier and more meaningful life. As the founder of A—SPACE, Australia’s first multidisciplinary meditation studio, he walks this truth en masse with a family of one heart, having regularly taught in New York, Los Angeles and throughout Australia. Manoj became Australia’s first lululemon global yoga ambassador, a role he uses to champion more accessible and inclusive wellness experiences for the under privileged and marginalised.

The following conversation was proudly initiated and inspired by lululemon.

Manoj Dias: It’s good to see you, brother. Thank you for coming to my place, visiting Melbourne today.

Tjimarri Sanderon-Milera: Thanks for inviting me here today bro. It’s been a minute.

M: It’s a pleasure. We’ve caught up intermittently at a few events through Lululemon over the last year, so it feels good to keep flowing on from where we’ve left off. There’s a lot of different places in which the work we’re doing intersects. [Over] the last few years a big focus for me, through meditation and mindfulness, has been exploring ways to take this to people and communities that don’t usually have access to them. For a long time, I’ve felt that wellness feels exclusive, right? You need a certain amount of money to go to a particular yoga studio or fitness studio. Even as we see more meditation studios, it feels like it’s available to a certain class, or demographic. There are communities that can really benefit from wellness, and I was really interested to find out from you, because I’ve got such a massive interest in Australia’s Indigenous culture. How would you and your communities really approach wellness?

T: We’ve always done things collectively or as a family when it comes to perspectives on education and health. Traditionally we’ve had our storytelling which is passed down. There is advice from elders, interconnectedness with family and community and even things like healing circles and other ceremonies. It’s complex because we have these traditions but we also live in a society not designed for them. [In] Aboriginal communities, we’ve been orientated towards sport, like AFL or NRL. They’re the main sports that Aboriginal people zone in on because that’s what they see. They think, ‘Oh, that’s all I can be good at, so I’m going to be a football player’. [This] is the reason why I chose not to play football and become a runner, but it’s been tricky. I would love to see Australian Aboriginal communities looking at alternative ways of being active and mindful and having that bit of wellness in their lifestyle that’s not just through football.

M: I think with minority communities, there are so many other priorities, right? Wellness almost falls to the bottom of that. But what I’m seeing, and you’ll probably agree, when it comes to the statistics around mental health… anxiety, depression, and suicide, it almost disproportionately affects minority communities.

T: Massively.

Tjimarri Sanderon-Milera: Thanks for inviting me here today bro. It’s been a minute.

M: It’s a pleasure. We’ve caught up intermittently at a few events through Lululemon over the last year, so it feels good to keep flowing on from where we’ve left off. There’s a lot of different places in which the work we’re doing intersects. [Over] the last few years a big focus for me, through meditation and mindfulness, has been exploring ways to take this to people and communities that don’t usually have access to them. For a long time, I’ve felt that wellness feels exclusive, right? You need a certain amount of money to go to a particular yoga studio or fitness studio. Even as we see more meditation studios, it feels like it’s available to a certain class, or demographic. There are communities that can really benefit from wellness, and I was really interested to find out from you, because I’ve got such a massive interest in Australia’s Indigenous culture. How would you and your communities really approach wellness?

T: We’ve always done things collectively or as a family when it comes to perspectives on education and health. Traditionally we’ve had our storytelling which is passed down. There is advice from elders, interconnectedness with family and community and even things like healing circles and other ceremonies. It’s complex because we have these traditions but we also live in a society not designed for them. [In] Aboriginal communities, we’ve been orientated towards sport, like AFL or NRL. They’re the main sports that Aboriginal people zone in on because that’s what they see. They think, ‘Oh, that’s all I can be good at, so I’m going to be a football player’. [This] is the reason why I chose not to play football and become a runner, but it’s been tricky. I would love to see Australian Aboriginal communities looking at alternative ways of being active and mindful and having that bit of wellness in their lifestyle that’s not just through football.

M: I think with minority communities, there are so many other priorities, right? Wellness almost falls to the bottom of that. But what I’m seeing, and you’ll probably agree, when it comes to the statistics around mental health… anxiety, depression, and suicide, it almost disproportionately affects minority communities.

T: Massively.

Manoj wears Lululemon LAB the Confluence Snapdown Silver Drop.

T: For me, when it comes to wellbeing, it’s still something that I’m working on myself. Even now, I meditate sometimes, I do yoga sometimes, but it’s still something that’s not completely concrete in my lifestyle and that’s just obviously because it’s never been normal for me to do so. But I do find myself increasing it every month. I’m going to be doing a mindfulness programme [this year]... Something that will help the kids I work with in changing their lifestyle for the better, which will be amazing to see.

M: Tell me about the programme you’re working on?

T: It’s through my work at the University of Adelaide. Basically, for students in grades 10-12, we encourage them to build up their skills of resilience, leadership, organisation and those essential life skills that will help them succeed in, essentially, the university world, which is not currently designed for Aboriginal people. This year I put my hand up and said, ‘I want to run something. It’ll include mindfulness, some core values, goal setting and so forth’.

For more, click through to watch the video series.

M: I think it’s really important, man… I just got back from three months in New York and some communities are really struggling to just meet the day-to-day expectations and pressures of life. But it’d be great if at some point in our lifetimes that we can see these practises, which I think is like basic friggin’ skills of how to notice your breath or how to be mindful of your emotions, be brought into our universities and schools because, man, when I was young, if I knew how to deal with my anger I might have been a very different person in the first portion of my life.

T: I feel you on that one.

M: I wasn’t really taught too much about it [Aboriginal culture] in school. But I’m really excited to learn more from you on how the Aboriginal people really value the concept of ‘community’ because. Correct me if I’m wrong here, but for me and people my age group growing up in cities like Melbourne, the desire to be part of something bigger than us is so massive, right? Our parents’ generation, maybe our grandparents’ generation, had things like churches, temples and monasteries. Whether you follow a religion or not, one beautiful thing it offers is this ability to come together with people that have a very shared belief or a shared intention and to feel not as alone as you might. You can be held in this space and you can feel like they’re your brothers and sisters. Does Aboriginal culture bring people together in that same way?

T: When it comes to Aboriginal communities, as I was saying it’s like everyone’s family. And we have very big families. I don’t even know how many ‘Nanas’ I’ve got. My Nana’s sisters and brothers are also my Nanas and my Grandpas and it goes down from there. My first cousins are actually my brothers, it just keeps rippling out. Having families like this creates this interconnected community. You go to a gathering and everyone’s just one big family, you’re always in a sense connecting and sharing culture.

M: Talk to me about the sharing of the culture. Coming from Sri Lankan Buddhist culture and growing up far North Queensland, for me, it wasn’t around celebrating how different I was. It was around trying to fit into the dominant culture and almost hiding my culture.

T: The main way it is seen across all Aboriginal cultures is [that] we are keeping our culture alive through songs, dance and art, this is really important to us. When you go to events hosted by Aboriginal people, like Survival Day, you have different dance groups, artists all coming together sharing their songs, their dances with younger kids and even non-Indigenous people. They’re opening their mind to Aboriginal culture by seeing these dances or the didgeridoo getting played in the most ridiculous way possible. The stories in the art blow your mind; there’s always something to learn. The stories help us navigate this world, this is that wellbeing I guess.

T: So what about you? You grew up in Queensland, which is known for being a very racist area in Australia.

M: It was hard out there!

T: How’d you manage and cope, growing up in that environment?

M: That’s a great question. A lot of what I do now is to create a sense of community, built on the foundations of mindfulness, meditation and spiritual practice. That really started for me growing up when I didn’t have a community. I was the only black kid in, what felt like, the whole town. It took me ‘til the age of 12 or 13 to actually see another person of my colour. When you’re teased and bullied for the way you look, as I said, you don’t really think too much about your culture and your community. Instead, you just want to fit into whatever’s going on. It took me up until my mid-20s to realise how much I had missed that in my life, and how much I had suffered, either through anxiety or stress. Now, the basis of my lineage of teaching and my meditation practise really stems from Buddhist meditation, and one of the cornerstones of our practice is called Sangha, which translates roughly to ‘community’. Sangha is one-third of the foundational practise of meditation. Buddha taught that we can find healing, awareness and awakening within these spaces where we don’t feel alone. We can explore life from that space. I think a lot of, especially mental health issues, and there’s research that goes to show this, stem from this feeling of being alone.

T: Plenty of times throughout my career, [I’ve felt] it to be a lonely world at the centre. You have to open your mind to go out and explore, and be able to find someone or people that aren’t going to make you feel lonely.

Sprinting is a solo sport. You’re training as a part of a squad, but for the most part, you’re training and competing for yourself, regardless if you’re in a national team or whatever. You want to get that 0.1 or a second quicker. The amount of mental space that takes up in your head is crazy and it gets very, very lonely. Even when you are at your peak of performance, you’re still just constantly wired to how lonely you actually are during that sport.

M: Because you’re also competing with the people that you’re in the community with…

T: I was training with three other guys - good mates now - but when I walk up to the start line, we’re not mates, and you think, ‘No, I’m going to beat them. It’s me and the clock here.

I don’t care what he runs, he doesn’t care what I run. I’m just running to win’. It really takes a mental toll after some time.

M: You have this culture of community that you’ve been brought up with, the Aboriginal sense of community, and there’s this sense of community in athletics. How do these two intersect in the work that you’re doing?

![]()

It’s like people are too scared to ask for help. They think that everything needs to be done

Sprinting is a solo sport. You’re training as a part of a squad, but for the most part, you’re training and competing for yourself, regardless if you’re in a national team or whatever. You want to get that 0.1 or a second quicker. The amount of mental space that takes up in your head is crazy and it gets very, very lonely. Even when you are at your peak of performance, you’re still just constantly wired to how lonely you actually are during that sport.

M: Because you’re also competing with the people that you’re in the community with…

T: I was training with three other guys - good mates now - but when I walk up to the start line, we’re not mates, and you think, ‘No, I’m going to beat them. It’s me and the clock here.

I don’t care what he runs, he doesn’t care what I run. I’m just running to win’. It really takes a mental toll after some time.

M: You have this culture of community that you’ve been brought up with, the Aboriginal sense of community, and there’s this sense of community in athletics. How do these two intersect in the work that you’re doing?

It’s like people are too scared to ask for help. They think that everything needs to be done

by themselves to succeed in life.

T: Community, for me, is a sense of hope and leadership as well, there are times where you are receiving from a community or giving. I’m reaching 30, so I’m at the point where I’m wanting to create a space where I’m a leader for younger generations, whether that be in the Aboriginal community or athletics. That’s where I’ve had the opportunity to coach the Aboriginal athletic squad. We’ve got 15 or 20 kids, and 13 of them are rocking up on a regular basis, which is amazing. They’re coming out Mondays and Wednesdays, they’re learning athletics, and they wouldn’t know it, but they’re learning about community. They’re learning about being organised for training, being healthy

and active. They’re just having fun. It’s crazy. Now, I can connect those two together.

M: Awesome.

T: What about you now? How have you managed to connect everything together?

M: Oh man, it’s interesting. When A-SPACE, my meditation studio, opened in 2016, I think we saw that people in Australia were curious about mindfulness and meditation. We started to notice that a lot of people were meditating in Australia, but they were usually doing it through apps.

T: Spotify meditation playlists right?

M: Right. YouTube and stuff like that, which is all great, but there was nowhere where you can ask the teacher a question or be around other people meditating. I met so many people that said it was kind of like a secret, ‘Oh, yeah. I meditate too’. Something to be ashamed of. With the studio, people will come together to have these really beautiful conversations. A community really started to form, and it became pretty obvious that people just don’t get this elsewhere. Our fore-fathers have always had a village to support them in their lives. These days it doesn’t feel like we have a village.

T: It’s like people are too scared to ask for help. They think that everything needs to be done by themselves to succeed in life.

M: I think that’s us as humans - our natural inclination. I genuinely believe, at our core, we are all good people, and given the opportunity, given our ability to calm our mind, each of us would be receptive to helping and to giving. Meditation can really help us to calm our minds to the point that we can feel into our bodies and feel into our hearts. Making it easier to connect with people, with ourselves. What are some of the challenges of creating a community? Because if it was super easy, everyone would do it, right?

T: Very true. I was lucky enough to have the support of Port Adelaide Athletics Club, where there’s a strong Aboriginal community. This year, they put an Aboriginal design on all their team uniforms and they’re really making stepping stones in how they want to support their local community. In that aspect, it was easy to put an Aboriginal athletic club together. Because we were the first ones to do it, the Sporting Commission of South Australia has gotten behind it. They were able to fund us; we’re able to pay for coaching, for the kids to compete every weekend, and give them a kit, healthy foods and everything. But It’s not always that easy.

M: Especially without funding, right?

T: Yeah. It was very surprising to get funding for the programme because athletics doesn’t have much funding at all. I didn’t get any funding in my career, unless I was going to be making the big finals on the regular... So, setting up a community can be hard work. You’re going to go through that period where you feel like you’re alone because no one’s getting behind you.

M: Especially without funding, right?

T: Yeah. It was very surprising to get funding for the programme because athletics doesn’t have much funding at all. I didn’t get any funding in my career, unless I was going to be making the big finals on the regular... So, setting up a community can be hard work. You’re going to go through that period where you feel like you’re alone because no one’s getting behind you.

M: Isn’t it ironic? I can definitely resonate with that. But I think it’s one of the challenges we face as community builders, is that it can sometimes feel very lonely in that process. Resources definitely help; being able to pay people to do little things. Having the ability to get someone to design a flyer and then getting the word of mouth actually out there...

T: It also comes down to the fact that we live in a very judgmental time as well. People don’t want to go out and feel judged.

M: Yeah. Wow. Where do you think that comes from?

T: Media. The media is constantly creating reasons for people to judge, for the smallest things. The media will always amplify things... So I guess that definitely plays a factor, but it also goes down to the presence of self-care. I’d love to hear about how you maintain balance in your life.

M: For me, it’s so important that my meditation practise is consistent and solid. It’s like the backbone of who I am as a human, outside of being a teacher. I try to maintain a daily practice. I study almost every second or third day and I stay connected to my teachers. I’m always trying to remain curious. How do you maintain your own running capacity when so much of your time, which usually goes into being an athlete, now goes into being a mentor?

T: It’s wild because my whole day is just jam-packed. I’m up at 4:30 or 5 in the morning to go for a run or to the gym. Making sure that I’m getting in that session before my work day’s even started.

M: Yeah, and I was going to ask you about that because this is something that I’m currently navigating. I didn’t realise at that point, as I was teaching all these classes, doing workshops and presenting so many talks that I myself was burning out. You know? And this was something that I find is paradoxical, where what you’re teaching essentially is causing you to suffer what you’re actually teaching people to heal from. What else do you wish people knew?

Being part of a meditation community really saved

my life at a point that I really needed it

TJ wears the lululemon LAB: Ashta Short Sleeve Tee Grey, Confluence Snapdown Silver Drop and the Confluence Pant Ink Blue. Manoj wears the Ashta Bomber Ink Blue and the Confluence Pant Ink Blue.

T: With Aboriginal communities specifically it’s... A lot of people don’t see the bigger picture of what happened 250 plus years ago [through colonisation]. They just see it as now. They don’t look at the past. Purely because they just don’t want to because I guess in the back of their head they know how bad it actually was.

M: Right, and people don’t really understand the effects of colonisation. And how have you seen that?

T: It set Aboriginal culture up for failure. We’d never had our eyes on any of the things colonisation brought - disease, alcohol, etc., so we never knew how to handle it. We didn’t know how to process things and it’s just a ripple effect from there.

M: I think these days we can see something and we just make up our own mind as to what has happened.

T: Yes, exactly...

M: Or have expectational questions like ‘why can’t they do this? Why can’t they do that?’ But I see it as intergenerational trauma leading people to behave the way they’re behaving.

T: Exactly. It’s the ‘shame’ factor as well. Through colonisation and slavery, it was put on Aboriginal people and across the globe, that if you’re black, you were essentially a slave and then you’d have that shame factor put over you.

That has just gone through generations and generations. Aboriginal kids are growing up, where they’re told they’re not going to be able to succeed because it’s a white man’s world. In the work that I do with the university, we’re creating a space where they’re getting out of their comfort zone, they’re breaking that shame factor to be able to go into a white university. At our univer-sity, there are 200 Aboriginal students, but there are about 30,000 students at the university.

TJ wears the Lululemon LAB:

Ashta Short Sleeve Tee Grey

That’s a big difference and we don’t want to set them up for failure. We want them to achieve their degree. Then they go on to further education or getting great jobs, so they can go out to benefit the communities. We need to understand what the conditions that are being put upon these people to feel what they are feeling and then look outside the box as to how to positively affect that. [There are things that are] quick and easy, that don’t involve us actually looking at ourselves in the process. I’d love to know how you get someone to explore meditation or being mindful?

M: When people say to me, ‘I’m not a meditator’. I ask them, ‘Do you cook?’ And they’re like, “Yeah, sometimes’. ‘Okay, what do you do when you cook?” And they’re like, “I don’t know, I chop the vegetables’. ‘But I’m guessing you also have to smell the ingredients and you’re touching all the different spices and things like that’. These little moments are what we call mindfulness. When you’re engaged through your senses in an everyday activity. You and me sitting here is a very mindful activity because you’re listening through all of your senses. You’re looking at my body language, you’re sensing what I’m sensing and you’re responding in a way and we’re connecting.

T: That it’s not as scary as you think. Someone might say, ‘I’m not a runner’, but I’d be like, ‘I’m sure you’ve run to the bus stop because you were late. There, you’re running. It’s not hard. It doesn’t have to be super fast. It can be at your own pace. It doesn’t need to have a stigma that if you’re not running fast, you’re not running.

M: I love that… how similar starting meditation is to starting running. Because the runs that I have gone on in my life, the four or five, there is this point within the first few minutes where I’m like, “I can’t do this.” My mind is going a million miles an hour, but then there’s something within you that says, ‘No, just keep going’. And then you come out of that whole experience and you’re like, ‘Oh, it wasn’t that bad, I actually feel Ok’.

T: Yeah, that’s happened to me as well. It was after work one day, I thought I’d go for a quick jog. Then I was like, ‘Oh, I’ll just keep going again’. I got to 10km and I felt good. I got back to the car and it had been 21 km’s. I was like, “’Oh dang. I’ve never run that far before’. I went from 10km to 21km. I had just gotten lost in running. Literally, just one step after another.

M: Like a flow state, you were just in the zone… Tjimarri, if we could look forward five years in time, what would you love to see happen with the community that you’re creating?

T: I’d love to see it as a stable thing. It’s only two nights a week at the moment. I’d love to see it eventuate into something where I am just coaching the senior squad that’s just dedicated to doing athletics and sprinting. Sprinting and running changed my life, so I want to help kids change their life. They’re sticking to it, and if I can do that in the next five years, that would be insane.

M: That’s beautiful.

M: Like a flow state, you were just in the zone… Tjimarri, if we could look forward five years in time, what would you love to see happen with the community that you’re creating?

T: I’d love to see it as a stable thing. It’s only two nights a week at the moment. I’d love to see it eventuate into something where I am just coaching the senior squad that’s just dedicated to doing athletics and sprinting. Sprinting and running changed my life, so I want to help kids change their life. They’re sticking to it, and if I can do that in the next five years, that would be insane.

M: That’s beautiful.

M: Similar to you. Being part of a meditation community really saved my life at a point that I really needed it, and, for me, my big goal with A-SPACE is that you can enter into it wherever that is in the world and feel a little less alone and have the hope that through the teachings and community, you can really heal and help yourself.

No matter how much you’re struggling with life or whatever’s presented to you, you’re not going to be alone. My big dream for A-SPACE is that people really get the opportunity to experience that, not just in Australia, but all around the world.

T: Man, love it.

M: Bro. It’s been fun.

T: It’s been real.