Childs Notes

The communication of movement, a movement of communication.

A discussion between Dr. Clare Lidbury, Nas Hosen & Rose Van Vijl, hosted by James Whiting.

This story features in Good Sport 05, available now.

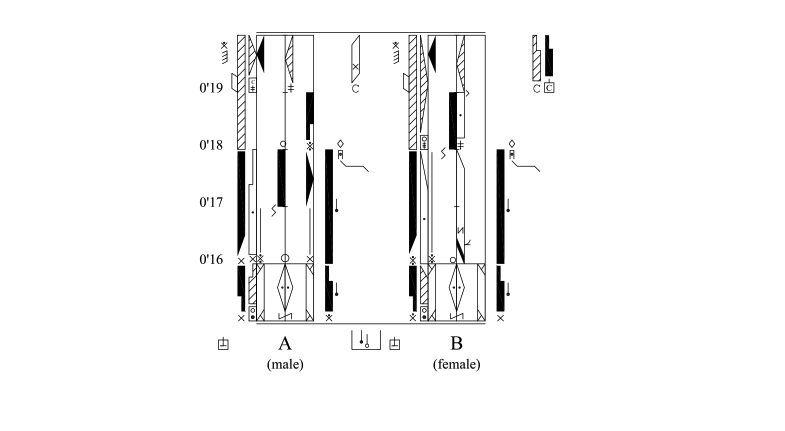

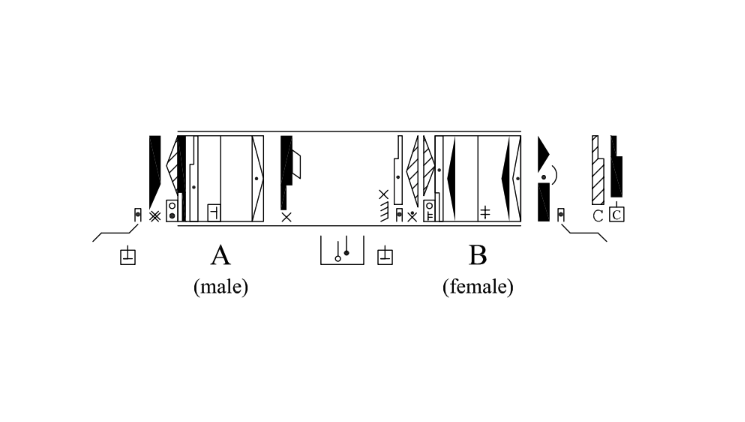

Labanotation is an extensive movement notation system that has left many a dance student bewildered in its wake. Developed by Rudolf Laban, the symbology resembles something akin to both semaphore and a traditional musical score. The system uses a progression of shapes along three individual axes – left, centre and right – to describe the sequence of any given movement. Just one of several forms of dance notation, it is renowned for its status as a laborious, yet comprehensive instrument: it is of almost equal interest to choreographers for its precision, as it is to graphic designers and artists for its entrancing aesthetic.

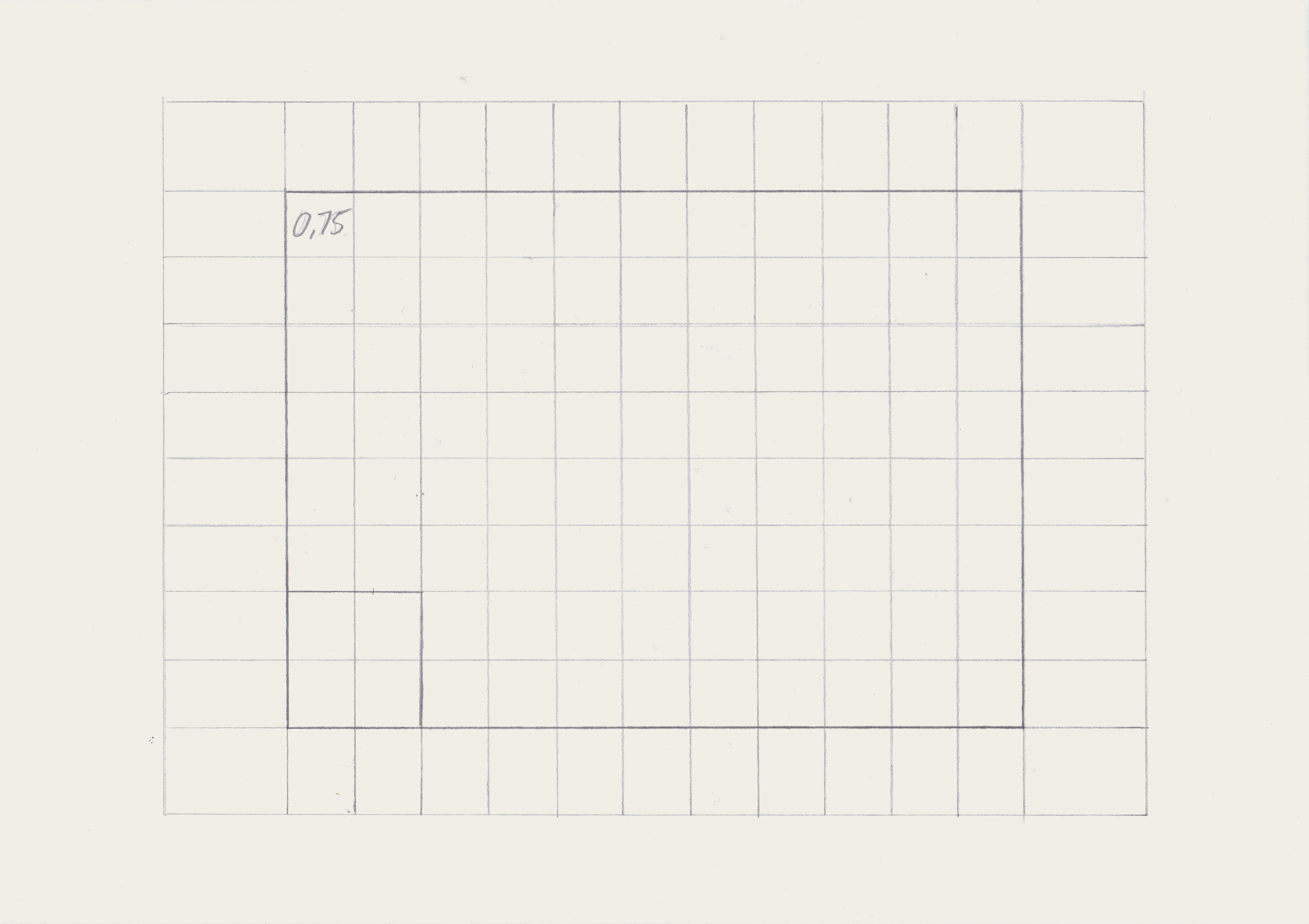

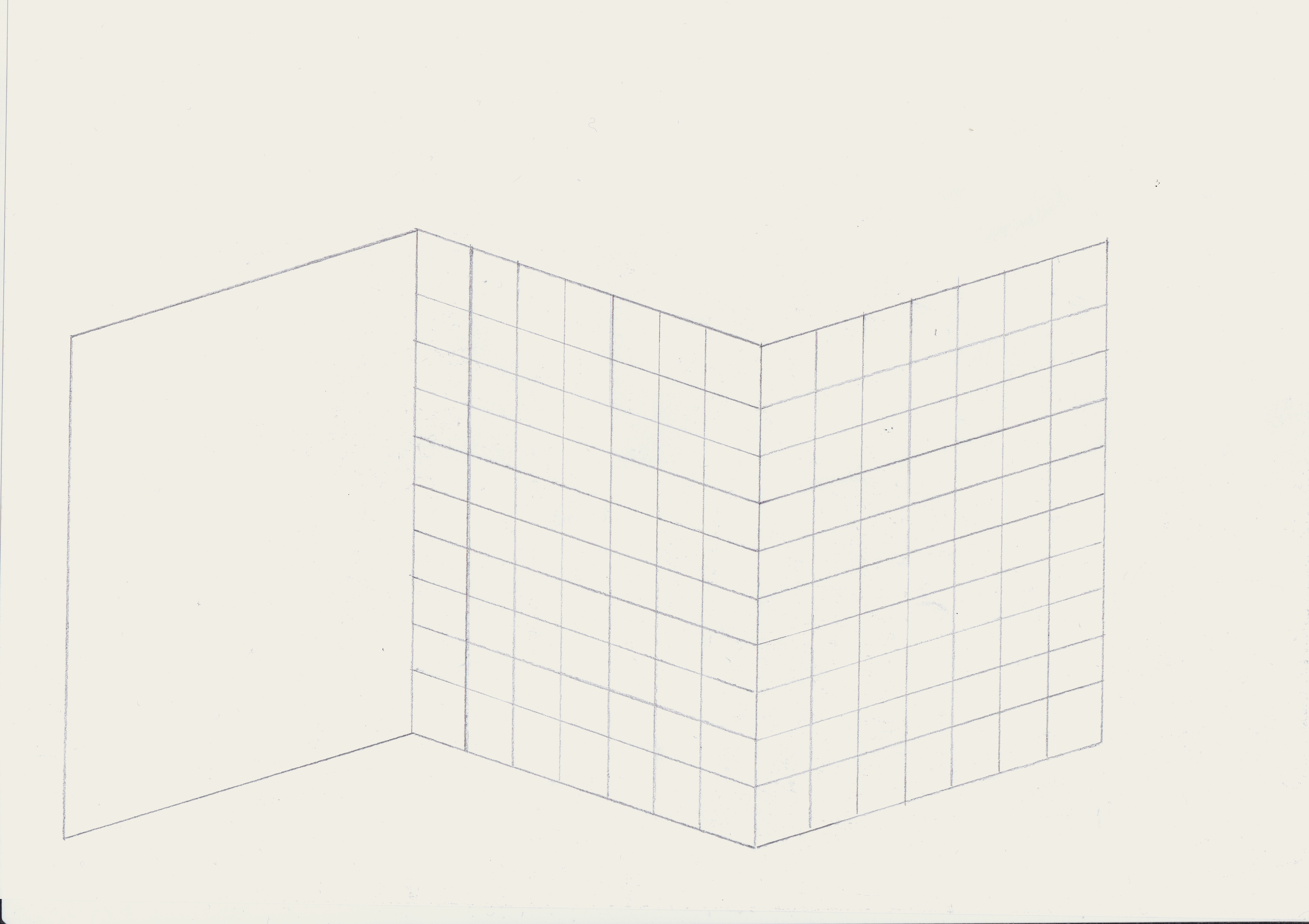

The potentially archaic system of notation formed an initial point of interest in the early stages of the work Reposition – an ongoing movement experiment that tests the potential capacity for a grid (consisting of words and numbers) to connect dancers in separate locations. The work was created by Rose Van Zijl, graphic designer and art director, and Nas Hosen, photographer and creative, who are based in Rotterdam and The Hague, respectively. Sharing a background in breakdancing, the project sparks thoughts of not only how movement is displayed to an audience, but of how the knowledge and the intention of movement is communicated between dancers – and perhaps more specifically, between teacher and student. We, the curious bunch, dove headfirst into the rabbithole of physical articulation, seeking out insights, answers, maybe some new dance moves. We were led to Dr. Clare Lidbury, Editor of the Laban Guild’s magazine, Movement, Dance and Drama, and the former Head of Dance at the University of Wolverhampton in the U.K.

Approaching the field of movement and dance from seemingly disparate vantage points, it was likely that the three would have some questions – and answers – for one another. We were right.

Labanotation

Rudolf Laban’s initial ideas for a movement notation system were worked on by Kurt Jooss, Sigurd Leeder and Dussia Bereska, and presented at the Essen Dance Conference in 1928. Later the work of Albrecht Knust and Ann Hutchinson Guest, in developing Kinetography Laban or Labanotation, was crucial. It’s function is to analyse and record human movement. The system continues to advance with the International Council of Kinetography Laban, promoting use of the system and overseeing the development of the system’s principles.

Rudolf Laban’s initial ideas for a movement notation system were worked on by Kurt Jooss, Sigurd Leeder and Dussia Bereska, and presented at the Essen Dance Conference in 1928. Later the work of Albrecht Knust and Ann Hutchinson Guest, in developing Kinetography Laban or Labanotation, was crucial. It’s function is to analyse and record human movement. The system continues to advance with the International Council of Kinetography Laban, promoting use of the system and overseeing the development of the system’s principles.

Key principles:

• The score is read from the dancer’s perspective, from the bottom upwards

• Direction of a movement is indicated by the shape of the symbols

• Level of a movement is indicated by shading within the direction symbols

• Speed of a movement is indicated by the length of a symbol

• The body part moving is indicated by where the symbols are placed on the stave

• The score is read from the dancer’s perspective, from the bottom upwards

• Direction of a movement is indicated by the shape of the symbols

• Level of a movement is indicated by shading within the direction symbols

• Speed of a movement is indicated by the length of a symbol

• The body part moving is indicated by where the symbols are placed on the stave

Clare: I danced all the time as a child – that was very much a part of my growing up. When I went to university, there were very few that offered dance as a degree subject. You could go for professional training, but I went to the only university offering dance at a degree level at that time, which was the University of Birmingham. That dance programme had been founded by Jane Winearls, a student of Sigurd Leeder, who had worked with Rudolf Laban.

Labanotation was a part of my degree, it was never anything I took much interest in. It was just something I could do. After I'd done my master's degree, the first job I got I had to teach notation. That's when I had to really get my head around it - to be one step ahead of the students. But my own research background, and practice-based work, is in my inheritance of Jooss and Leeder’s work - I can't call it the “Jooss Leeder Method”, because I don't have any of their certifications, or diplomas, or anything like that – but that's the basis of my work.

Good Sport: Did you continue to dance after you started teaching Labanotation? Did you find it quite laborious in practice?

C: Yes. We had a company that came out of the university when I was there. So, I was dancing with that for quite a long time. Labanotation was only ever one element of what I taught. Labanotation is laborious but was never a shorthand though, that was never the intention of it. And although not many people are studying it or using it, the system is still being developed by its devotees. I don't know if Labanotation is taught where either of you guys are, but in the UK I teach it, and I know one other teacher who's using it. Twenty years ago, most students would have studied Labanotation.

GS: Rose and Nas, you came to dance through breaking, and in that scene you're learning together as a crew: swapping and sharing moves instead of referring to a formal choreography. How did Labanotation come into your awareness?

Rose: For me, it was only when I went to art school for graphic design. I have a typographic approach and started to look for similarities between my design and dance practices. Before that, during my ten years of breaking, I’d never heard of Labanotation.

Nas: What I’ve experienced with dancers is that a lot of them write their choreography or set of movements during dance practice – they just make quick scribbles. Sometimes they forget what they’ve written, but still have to try to understand it, so they end up interpreting what they wrote again in a new way.

Labanotation was a part of my degree, it was never anything I took much interest in. It was just something I could do. After I'd done my master's degree, the first job I got I had to teach notation. That's when I had to really get my head around it - to be one step ahead of the students. But my own research background, and practice-based work, is in my inheritance of Jooss and Leeder’s work - I can't call it the “Jooss Leeder Method”, because I don't have any of their certifications, or diplomas, or anything like that – but that's the basis of my work.

Good Sport: Did you continue to dance after you started teaching Labanotation? Did you find it quite laborious in practice?

C: Yes. We had a company that came out of the university when I was there. So, I was dancing with that for quite a long time. Labanotation was only ever one element of what I taught. Labanotation is laborious but was never a shorthand though, that was never the intention of it. And although not many people are studying it or using it, the system is still being developed by its devotees. I don't know if Labanotation is taught where either of you guys are, but in the UK I teach it, and I know one other teacher who's using it. Twenty years ago, most students would have studied Labanotation.

GS: Rose and Nas, you came to dance through breaking, and in that scene you're learning together as a crew: swapping and sharing moves instead of referring to a formal choreography. How did Labanotation come into your awareness?

Rose: For me, it was only when I went to art school for graphic design. I have a typographic approach and started to look for similarities between my design and dance practices. Before that, during my ten years of breaking, I’d never heard of Labanotation.

Nas: What I’ve experienced with dancers is that a lot of them write their choreography or set of movements during dance practice – they just make quick scribbles. Sometimes they forget what they’ve written, but still have to try to understand it, so they end up interpreting what they wrote again in a new way.

you work with the grids to start breaking them

[Breaking] is really monkey see, monkey do. In the context that hip-hop breaking started in the USA, we [in Europe] got it from television. So, what we saw, we tried to copy and also make something new. And for me, when it came to the competition or performance context, then it became interesting for me to write down a certain pattern of moves, in a way [only] I myself understood. So, it was, let's say, child’s notes.

C: One of the first tasks I set, when I start teaching Labanotation, is to teach a really simple sequence. Four walks forward, four walks back, side close, side close, and then side close side going the other way. I ask students to write it down in some form, and for some of them that's a real wake up call because they think they've captured it, and it makes perfect sense to them, but not to anybody else. It's when you want to give that material to someone else, and you're not able to physically demonstrate it –– that's when notation is extremely useful.

N: In the context of the break-dance scene, performing is a unique way to present yourself as a person or as a dancer. And normally, it's not good to give your language away to somebody who you're competing with.

C: One of the first tasks I set, when I start teaching Labanotation, is to teach a really simple sequence. Four walks forward, four walks back, side close, side close, and then side close side going the other way. I ask students to write it down in some form, and for some of them that's a real wake up call because they think they've captured it, and it makes perfect sense to them, but not to anybody else. It's when you want to give that material to someone else, and you're not able to physically demonstrate it –– that's when notation is extremely useful.

N: In the context of the break-dance scene, performing is a unique way to present yourself as a person or as a dancer. And normally, it's not good to give your language away to somebody who you're competing with.

So, writing it down is not the intention. It's more a focus to only share the movement during the competition – that surprise element is self presentation. The way to develop yourself as a dancer is to find your own way. Something that has come along with [the growth of] the culture is that everything is being recorded. By having all this documentation, it's becoming harder for the dancers to come up with new sets of movements, and to be surprising at every new event.

C: In theory, Labanotation can deal with that because there is no one way of writing something. Six notators in a room – they can all write a movement differently, depending on their own experience of the movement, how they see it and what they think [the choreographer] wants to be communicated through that movement. What they think is the intention of the movement is reflected in the many nuanced ways of writing that particular movement.

GS: Is there a similar sentiment in the classical dancing world where you wouldn't want that dance to get into someone else's hands? Was it [ever] that competitive, or secretive, do you think?

C: In theory, Labanotation can deal with that because there is no one way of writing something. Six notators in a room – they can all write a movement differently, depending on their own experience of the movement, how they see it and what they think [the choreographer] wants to be communicated through that movement. What they think is the intention of the movement is reflected in the many nuanced ways of writing that particular movement.

GS: Is there a similar sentiment in the classical dancing world where you wouldn't want that dance to get into someone else's hands? Was it [ever] that competitive, or secretive, do you think?

C: There was very much a sense of that. So, I'm not sure if this is true or not, but what I was told was that Martha Graham, that iconic figure, allowed her work to be notated, but no one was allowed to reconstruct them. She wanted her works recorded for posterity, but only somebody who'd had her training and knew that work inside out was allowed to actually use the score, because she didn't want the work distorted or misinterpreted. Which is fine on one level, but if no one else can access it, what's the point?

GS: Clare, that reminds me of something you said when we last spoke –

“Is it still a language if no one speaks it?” Which is such a profound thought. It makes you wonder, well, what is the border of communication in that respect?

C: The original function of Labanotation was to capture the choreography of a choreographer, so that it could be given to other dancers who would be able to learn it from the score. The notator is listening to what the choreographer is saying, and what they're asking of the dancers, as well as looking at and analysing the movement. And that helps them to write it down in specific ways.

GS: Clare, that reminds me of something you said when we last spoke –

“Is it still a language if no one speaks it?” Which is such a profound thought. It makes you wonder, well, what is the border of communication in that respect?

C: The original function of Labanotation was to capture the choreography of a choreographer, so that it could be given to other dancers who would be able to learn it from the score. The notator is listening to what the choreographer is saying, and what they're asking of the dancers, as well as looking at and analysing the movement. And that helps them to write it down in specific ways.

So, writing it down is not the intention. It's more a focus to only share the movement during the competition – that surprise element is self presentation.

GS: Does that mean that a dance is only written once initially by a notator? Does the dance get rewritten at all?

C: Yes it does, because dances evolve over time. It's an interesting process, because it's not always clear who causes the evolving. ‘The Green Table’ for example, by Kurt Jooss, was notated by Ann Hutchinson-Guest in 1938. She wrote the score, gave it to Jooss and he used it until the 60s. Then it was decided that that score didn't have enough detail. In the process of re-writing the score, dancers who had performed it over time brought their memories of what they thought the movements were, and so Jooss and his daughter made decisions about what they wanted and arrived at the definitive version - “This is what The Green Table is.” But if you compare the score that was finally published in 2001 with that first score, there are some big differences in terms of the sequencing, the pacing and the dynamics of the movements. We don’t know whether that's because Jooss developed the material over time, adapting it to the dancers who were taking the roles, or from the dancers' bodies as they remember them. There's so much more to capturing something than just what’s in the body.

GS: In that sense does a teacher's physical language carry on through the school that they're teaching at? As if you're passing on something similar to a dialect.

Claire: It does, but the people who are passing it on are the human. As a teacher you pass on the things that worked on your body, so in turn there are things that you don't teach that were part of your teacher's vocabulary, because they don't fit you.

C: Yes it does, because dances evolve over time. It's an interesting process, because it's not always clear who causes the evolving. ‘The Green Table’ for example, by Kurt Jooss, was notated by Ann Hutchinson-Guest in 1938. She wrote the score, gave it to Jooss and he used it until the 60s. Then it was decided that that score didn't have enough detail. In the process of re-writing the score, dancers who had performed it over time brought their memories of what they thought the movements were, and so Jooss and his daughter made decisions about what they wanted and arrived at the definitive version - “This is what The Green Table is.” But if you compare the score that was finally published in 2001 with that first score, there are some big differences in terms of the sequencing, the pacing and the dynamics of the movements. We don’t know whether that's because Jooss developed the material over time, adapting it to the dancers who were taking the roles, or from the dancers' bodies as they remember them. There's so much more to capturing something than just what’s in the body.

GS: In that sense does a teacher's physical language carry on through the school that they're teaching at? As if you're passing on something similar to a dialect.

Claire: It does, but the people who are passing it on are the human. As a teacher you pass on the things that worked on your body, so in turn there are things that you don't teach that were part of your teacher's vocabulary, because they don't fit you.

GS: What do you think is missed as you pass a dance down in teaching? Do people just adapt, and try to mimic that teacher as closely as possible?

C: I think it really depends on what school of dance you're in. So, if you were to look at footage of Martha Graham at her peak in dancing, and then to look at somebody who's a pupil of a pupil of Martha Graham, you'll find a skeleton that's quite similar, but the intention with which Graham danced will be very different from that of the last generation students, because everything around you has an impact. How you have received that work isn’t necessarily how you pass it on.

GS: Do you think physical limitations in terms of actual physique and geometry of the body, they place a ceiling on how closely you can mimic somebody?

C: Using Martha Graham again, she made her technique for her body, and the bodies who are like hers can do it. So, particularly when she first started, men found the technique very difficult because their bodies weren't ready for it. Whereas now, male dancers have a much wider training so they can do most things. You wouldn't be able to say that men can't do Graham's work anymore, because the whole nature of training has changed so much.

C: I think it really depends on what school of dance you're in. So, if you were to look at footage of Martha Graham at her peak in dancing, and then to look at somebody who's a pupil of a pupil of Martha Graham, you'll find a skeleton that's quite similar, but the intention with which Graham danced will be very different from that of the last generation students, because everything around you has an impact. How you have received that work isn’t necessarily how you pass it on.

GS: Do you think physical limitations in terms of actual physique and geometry of the body, they place a ceiling on how closely you can mimic somebody?

C: Using Martha Graham again, she made her technique for her body, and the bodies who are like hers can do it. So, particularly when she first started, men found the technique very difficult because their bodies weren't ready for it. Whereas now, male dancers have a much wider training so they can do most things. You wouldn't be able to say that men can't do Graham's work anymore, because the whole nature of training has changed so much.

There's so much more to capturing something than just what’s in the body.

GS: So, does that occur in your experience Rose, or do you create for your own physical ability?

R: For me, breaking is really masculine. And I think for me, it has always been this way, particularly in aspects such as ‘powermoves’, which refer to moves that require a lot of muscle strength, speed and a feel of momentum. A lot of traditional break moves, especially ‘powermoves’, require a lot of physical strength and traditionally boys would be more encouraged to practice them than girls. I started when I was ten, and I rarely saw or practiced with other B-Girls, so instead I would mimic male bodies. Sometimes I could see the boys around me pick up these powermoves really easily, so I would have to find a way to adapt, and that influences your style.

Later on, when I became a bit older, I noticed that I was mimicking something that didn't connect with my body. By that time I was very influenced by B-Girls like A.T. from Finland and Ayumi from Japan. Now there are many women of whom great powermoves are their signature. For example the windmills done by B-Girl Bubbles, who was the first B–Girl in the UK. Their styles showed that it does not matter what you do – but how you do it; by paying attention to detail, rhythm and flow. In a lot of ways the same stance applies to my design practice too.

C: I think that notion of masculinity is really interesting. It's quite interesting in the UK when children first go to dance classes, boys and girls are generally taught together. And then there comes a time when the classes are separated. So, men learn to do much bigger jumps and the girls do footwork and smaller stuff. And at a grassroots level, there are girls saying, "Well, why can't I learn those big jumps?". Now the dance training boards are having to rethink their syllabuses to allow that work to go to everybody, because in any other aspect of life, it wouldn't be acceptable to say ‘you can't do that because you're a girl’.

R: And there are girls who do really big power moves. It doesn't say anything about gender.

N: I’ve noticed that newer generations of B-Girls are able to do powermoves more easily since they have been encouraged to practice them at younger ages.

C: The analysis of the movement allows us to see what it is that makes it masculine – that would be a really interesting part of the notation process. And I suspect that it has to do with the actual shapes that the body is making and the rhythm with which it's done. I see that everything would be done in a very rigid, rhythmical manner – everything is an impact, or it happens on a beat if you like. Whereas if you were to be doing something that was off the beat, you could see that as a contrast, and maybe that would be considered more feminine. The physical strength required to do that movement – if you don't have that muscle tension – then it's not that same masculine movement.

N: Rose to add on what you said earlier about creating for your own physical ability, by finding your own way of movement, you get known for [your own form of] dancing, how you dance. It is like an eternal process. And Hip Hop culture – how you first try to fit into that culture and [seeing] what is commonly done in dance, you then [have to] try to find yourself in it.

R: For me, breaking is really masculine. And I think for me, it has always been this way, particularly in aspects such as ‘powermoves’, which refer to moves that require a lot of muscle strength, speed and a feel of momentum. A lot of traditional break moves, especially ‘powermoves’, require a lot of physical strength and traditionally boys would be more encouraged to practice them than girls. I started when I was ten, and I rarely saw or practiced with other B-Girls, so instead I would mimic male bodies. Sometimes I could see the boys around me pick up these powermoves really easily, so I would have to find a way to adapt, and that influences your style.

Later on, when I became a bit older, I noticed that I was mimicking something that didn't connect with my body. By that time I was very influenced by B-Girls like A.T. from Finland and Ayumi from Japan. Now there are many women of whom great powermoves are their signature. For example the windmills done by B-Girl Bubbles, who was the first B–Girl in the UK. Their styles showed that it does not matter what you do – but how you do it; by paying attention to detail, rhythm and flow. In a lot of ways the same stance applies to my design practice too.

C: I think that notion of masculinity is really interesting. It's quite interesting in the UK when children first go to dance classes, boys and girls are generally taught together. And then there comes a time when the classes are separated. So, men learn to do much bigger jumps and the girls do footwork and smaller stuff. And at a grassroots level, there are girls saying, "Well, why can't I learn those big jumps?". Now the dance training boards are having to rethink their syllabuses to allow that work to go to everybody, because in any other aspect of life, it wouldn't be acceptable to say ‘you can't do that because you're a girl’.

R: And there are girls who do really big power moves. It doesn't say anything about gender.

N: I’ve noticed that newer generations of B-Girls are able to do powermoves more easily since they have been encouraged to practice them at younger ages.

C: The analysis of the movement allows us to see what it is that makes it masculine – that would be a really interesting part of the notation process. And I suspect that it has to do with the actual shapes that the body is making and the rhythm with which it's done. I see that everything would be done in a very rigid, rhythmical manner – everything is an impact, or it happens on a beat if you like. Whereas if you were to be doing something that was off the beat, you could see that as a contrast, and maybe that would be considered more feminine. The physical strength required to do that movement – if you don't have that muscle tension – then it's not that same masculine movement.

N: Rose to add on what you said earlier about creating for your own physical ability, by finding your own way of movement, you get known for [your own form of] dancing, how you dance. It is like an eternal process. And Hip Hop culture – how you first try to fit into that culture and [seeing] what is commonly done in dance, you then [have to] try to find yourself in it.

R: I know, and that’s something that also translates into my design practise. You start working with grids, and then after, you know the grids, so you work with the grids to start breaking them.

N: Clare, do you think this language, this documentation, will exist for a long time, and do you think there will be [any further] development?

C: Well, I think that language will exist because there are some nerdy people like me who are fascinated by the whole process of how you can capture movement in symbols. There are fewer, and fewer people who read it and that is partly because society has changed. We want instant access to everything. If I want to know what a dance looks like, I can look on YouTube and find it in seconds, whereas going through the process of looking at a score, and trying to work out what that movement means, is a much longer process.When I work with students some of them just go ‘I’m not interested, I can't deal with this’ – it's much too hard. But some of them are really fascinated by the idea that you can write movement down in symbols. If you think about it in relation to music, think where music would have been if we had never developed a notation system.

N: Definitely.

N: Clare, do you think this language, this documentation, will exist for a long time, and do you think there will be [any further] development?

C: Well, I think that language will exist because there are some nerdy people like me who are fascinated by the whole process of how you can capture movement in symbols. There are fewer, and fewer people who read it and that is partly because society has changed. We want instant access to everything. If I want to know what a dance looks like, I can look on YouTube and find it in seconds, whereas going through the process of looking at a score, and trying to work out what that movement means, is a much longer process.When I work with students some of them just go ‘I’m not interested, I can't deal with this’ – it's much too hard. But some of them are really fascinated by the idea that you can write movement down in symbols. If you think about it in relation to music, think where music would have been if we had never developed a notation system.

N: Definitely.

C: Music in itself has moved way beyond the conventional way of writing music down. But all that history of music just wouldn't be there. We may have lost so much dance because we have had no way of capturing or recording it. And what works we have got recorded in notation are really important. What is difficult with a Labanotation score is to be really sure that what you're reconstructing is what the choreographer intended. So, when I'm working, or when I go to a score by a particular choreographer, I can't just read the score. I have to know about their technique, their way of working, their methodology, so that I can inform my reading of the score.

N: It's very interesting, because the root of Labanotation is to pass on what has been made, which made me think about passing on something that I’ve made.

And this is very important, especially in Hip-Hop culture, and what you have mentioned of classical dance. Labanotation, how does it survive alongside video documentation?

C: You don't need to have a video of the score you're working on, because quite often those two things will be in conflict. The video is of a performance and perhaps not of the choreographer's intention.

N: It's very interesting, because the root of Labanotation is to pass on what has been made, which made me think about passing on something that I’ve made.

And this is very important, especially in Hip-Hop culture, and what you have mentioned of classical dance. Labanotation, how does it survive alongside video documentation?

C: You don't need to have a video of the score you're working on, because quite often those two things will be in conflict. The video is of a performance and perhaps not of the choreographer's intention.

R: Clare, what you mentioned earlier made me think that since breaking comes from freestyle, it means that often choreography, notation, and repeating the same thing many times, is not helpful. We do repeat our movements during practice in order to build muscle memory but what’s interesting is that when freestyling, dancers often accidentally fall back into the moves that are most secured in that muscle memory – just like designers fall back to rules and grids. Although, I believe those grids and perhaps Labanotation too are utilised in order to uncover or inform a way of looking.

C: I mean, Labanotation is a process of fixing, and it's not going to work for every dance form. Not all dance forms are about that. Some aren't meant to be counted and in that process of capturing you undermine what that dance was about. When I'm teaching, I really try to stress that it's about moving. It's not a theoretical exercise where you’re just intellectualising and writing stuff down, because for dance students, if it's just theoretical, it has no value to you. If you could show how it works in practice, and how it clarifies your thinking about the dance material, then it has purpose.

C: I mean, Labanotation is a process of fixing, and it's not going to work for every dance form. Not all dance forms are about that. Some aren't meant to be counted and in that process of capturing you undermine what that dance was about. When I'm teaching, I really try to stress that it's about moving. It's not a theoretical exercise where you’re just intellectualising and writing stuff down, because for dance students, if it's just theoretical, it has no value to you. If you could show how it works in practice, and how it clarifies your thinking about the dance material, then it has purpose.

Reposition Film 2 from homefoodstories on Vimeo.